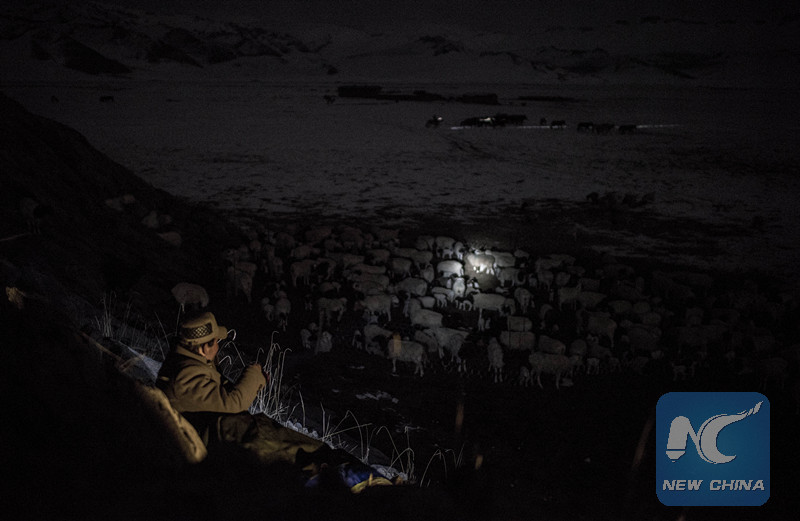

Shepherding the flock on the snow-covered grassland.

Birth and death walk side by side among Dilai's flock.

It's already April, but the Bayan Bulag grassland shows no sign of spring. For three days, Dilai and his family haven't seen a ray of sunshine but dark clouds and snowflakes. Pregnant ewes have to paw at the snow-covered ground to look for grass, while newborn lambs shiver in the wind.

Bad weather is the last thing herdsmen wish to see during the breeding season, the busiest and most important month of a year.

Despite modern farming technology, Mongolian herdsmen still preserve the tradition of grazing and migrating on the Bayan Bulag grassland in Bayingol Mongolian Autonomous Prefecture, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Dilai, 50, has been shepherding on the fertile grassland for decades. The flock of 200 sheep he took over from his father has expanded to 1,000 sheep. But this year, they have been caught with snow. More than 5,000 livestock have been killed by coldness in Bayan Bulag in April.

Dilai's nephew Qimti Cering watches for a newborn lamb.

Despite the bad start, the whole family are trying their best but have prepared for the worst.

Every day, Dilai and his eldest son Dovton inspect the flock on horseback, while Dilai's nephew Qimti Cering, who has come along with his wife to help, watches for the newborns abandoned by their mothers.

Dilai drives the newborns back to the flock.

A lamb struggles to get on its feet and tumbles all the way to its mother. But when it finally reaches the ewe, the mother gives out an angry bleat and dodges its child. The lamb approaches again, only to be knocked over by the irritated mother.

It is the fourth time that the lamb has been rejected by its mother. The ewe snorts and runs away, leaving the baby trembling on the ground.

A newborn lamb is left behind and shivers in the snow.

Coldness and hunger have deprived the ewes of motherhood. Some first-time mothers don't know how to take care of their babies, so some lambs are abandoned and can't survive without herdsmen's help.

To milk the lambs, the herdsmen would hold or bind the front legs of the mother so that the baby can reach the nipples.

An abandoned lamb is fed with the help of herdsmen.

A mother sheep licks to remove the caul wrapping its baby.

A mother sheep which keeps losing its child is tied with its baby on their legs.

As the night falls, the family are getting anxious. Dozens of lambs are expected to be delivered overnight. Without timely care, the babies would die quickly after birth.

Dilai is anxious to find the mother of the lost lamb before sunset.

The family hurry the flock back to the closure before it gets dark.

The shepherds match the mother and child while hurrying the flock back to the closure before sunset.

Dilai and Qimti Cering take on the night watch. Without heating, they have to spend the night in the open closures. The only lighting at hand is a flashlight. For the whole month, they have to spend the nights in the closure to keep an eye on pregnant sheep, which are to deliver anytime, and to prevent them from running away to labor elsewhere.

Dilai's eyes become bloodshot after he stays up for nights. He heads back to work after a hasty meal.

The whole family's income depends on the newly bred lambs in the breeding season, so they have to take good care of them even if they don't eat or sleep, says Dilai. Wrapped in a quilt, he huddles himself up beside the closure, waiting and listening attentively.

Dilai spends the night near the closure, watching his flock closely.

The flock in the night.

Dilai's wife Tuya prepares supper at 11:00 pm. Only during the supper can the whole family get together after a day's work.

Snow is used for cooking.

It is not the first storm that Dilai has met with, but he has never thought of leaving the grassland. Dilai's wife Tuya remembers that they had only a yurt, a bed and an offering table when they married. But their years' hard work has paid off. Now they have bought their children houses and cars in town.

Dilai and his wife Tuya in front of their home.

Apart from 10,000 yuan (about 1,400 U.S. dollars) subsidized by the government annually, Dilai earns 300,000 yuan every year by grazing.

"I'm a shepherd. Herding on the grassland is all my life," Dilai says. "I won't leave my flock until I'm too old to ride my horse or walk."

That's why 26-year-old Dovton decided to stay with his parents after he graduated from high school. He has chosen to undertake the obligation as the eldest son of the family and pass on his father's career, so that his two younger brothers have the chance to see the world outside.

"My parents can't leave their flock. They have to take care of the animals by themselves, and I want to take care of them. That's why I stay," he says.

Dovton overlooks his flock and home. He says he had good grades at school, and he should go to college if it were not for his parents.

As the night ticks away, another dozen of lambs have been born. Most of them are healthy, while some are in critical condition.

A lamb is too weak to open its mouth. It is motionless even if the herdsman dropped the milk into its mouth.

Qimti Cering has worked on it for half an hour, but the lamb's breath becomes weaker and weaker.

Vultures and crows nearby have flown to the closure, waiting.

The lamb fails to make it. Death won.

Dilai drives the flock down from the hill.

A new day has arrived, though the sun hasn't come out and snowflakes continue to float in the air.

Dilai believes all lives on the grassland, born on a sunny day or a snowy day, have their own destiny, just as he is destined to be a shepherd.

That's the reason why he preserves the ancestral tradition of shepherding, he says.

(All photos by Jiang Wenyao)